The Art of Visual Listening 2: Why Is Art?

(Posted on Wednesday, January 4, 2017)

Liberty Leading the People by Eugene Delacroix commemorates the overthrow of King Charles X of France in 1830

The Purpose of Art

Not only is art everywhere (as noted in my introduction to this series, What is Art?), but research suggests our species, Homo sapiens, has been making art for at least 100,000 years. So art has been everywhere for a long time. But the big question here is why. Why are human beings compelled to make art and, for the objectives of this blog series, how does knowing the answer to that help us evaluate art?

The overarching purpose for all art is communication. Whether anyone is out there to receive the message or not, art is still sending it. So what types of messages have we been compelled to send over time? What specific communicative purposes does art fulfill?

Below is an exploration of some of the basic reasons art is made and how understanding those reasons can help us evaluate it. You will notice as you read, that these purposes rarely stand alone, but instead overlap one another, communicating multiple messages.

- Practicality: designs intended to enhance the functionality of life

One reason for making art is to use it. People began making things like baskets and blankets because they were useful in everyday life.

The same is true of chairs, for example. And although they are made to fulfill one basic function, they come in thousands of different forms. Why is that? Well, while the primary purpose of a chair is to provide seating, there are many other reasons to create a particular chair in a particular way. Knowing these different reasons and seeing how well the chair fulfills them, can help us assess the chair’s quality.

The first step in evaluating the quality of a chair is to determine how well it fulfills its primary function. Can we tell it is a chair? Is it big enough to sit on? Is it sturdy enough? Can we sit on it without sliding off? If the answers to these questions are “yes,” we know the basic reason for the chair has been communicated and accomplished, and so, on this primary level, we can judge it as a good chair.

Look at the three chairs below. Let’s assume they all fulfill their basic purpose of providing seating. They’re recognizable as chairs, they’re big enough, study enough, and supportive enough, so they’re all good chairs. But, how do we judge their quality beyond that?

One way is to discover other reasons why the chairs were made. We can do this by looking at their differences and listening to what those differences tell us.

One chair invites us to, “relax outside in the back yard;” another urges us to, “snuggle down inside with a good book;” while the third says, “sit down, but don’t stay long.” So an artist can design a chair not simply as a place to sit but as a place to sit in a certain way. How well the chair communicates that message and then fulfills that message helps us to evaluate the quality of the chair even further.

For example, if that blue overstuffed armchair above turned out to be stiff as a board when you sat in it, you would be disappointed. The chair communicated comfort but didn’t deliver on it’s promise. It fulfilled its primary purpose (you know what it is and can sit in it) but not it’s other purpose (to be comfortable). We can now begin to assess this chair as having issues with quality.

So the point here is this, there can be layers of reasons why artists make art and, as evaluators, it helps to know as many of those reasons as possible so we can determine how well the art has fulfilled its purposes which, in turn, helps us to evaluate its quality.

- Abstract Concepts: to communicate ideas and beliefs

Besides making art for practical uses, we also make art to communicate concepts of all kinds: philosophical, religious, political…

Take the pyramids of ancient Egypt for example. They were created as tombs for the Pharaohs (or kings) whom the Egyptians worshiped as divine. According to their religion, after a Pharaoh died, his spirit lived on for eternity and needed the same things in the afterlife as it did in life.

So, the primary purpose of the massive stone structure below (the Pyramid of Khufu at Giza, built about 4,500 years ago) was a practical one–to be a tomb.

But another purpose was to communicate the religious idea of everlasting existence. And a third purpose was for the tomb to actually exist everlastingly. So, how well does this pyramid live up to its practical and conceptual purposes?

We know the king was buried here along with his possessions, which tells us the structure was designed well enough to fulfill its primary purpose. As a four-sided pyramid (the most stable of all geometric forms) built with two million stone blocks (the largest one weighing eighty tons), the structure also clearly communicates the idea of permanence, of eternal existence. And since this tomb is still standing after 4,500 years, I think we can safely say it not only embodies the concept of permanence but has been about as permanent a human-made structure as any on earth so far. So, now that we know how well the pyramid fulfills these purposes, we have some understanding of the quality of the work. (1)

- Commemoration: to record, document, extol/to impress

The Egyptian pyramids also had other purposes. Besides being permanent tombs and communicating the religious idea of eternal life, they commemorated the divine kings whose tombs they were. And, through their monumental size, they communicated the immense power of those kings, impressing all who saw them.

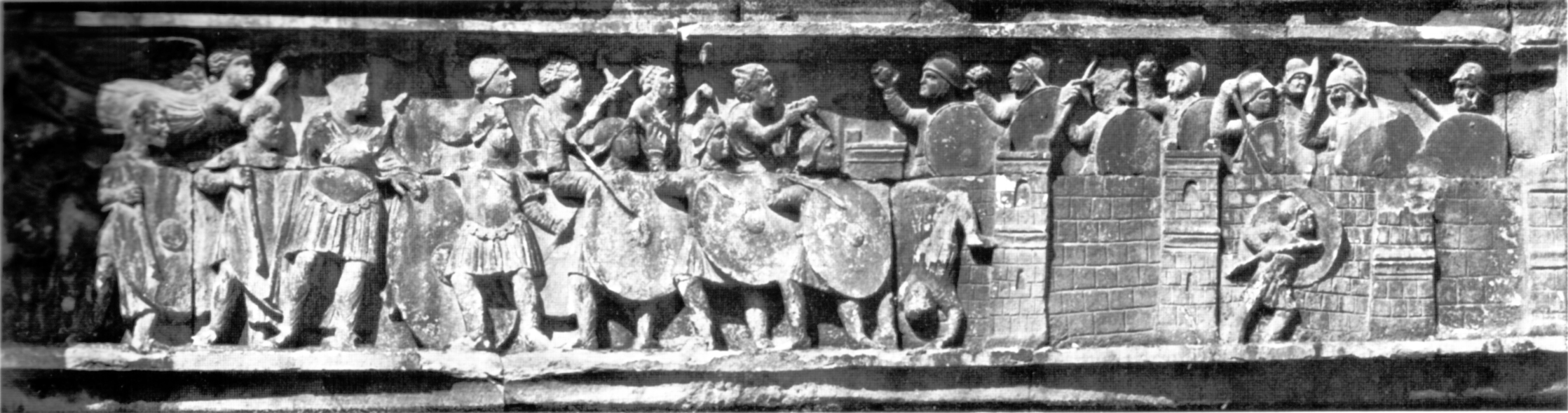

Another example of an artwork designed to commemorate and impress is the Arch of Constantine. It was built over 1,700 years ago to memorialize Constantine’s victory over his rival, Maxentius, making him the sole emperor of the Western Roman Empire. We know about this historic event today partially because of this commemorative arch with its inscriptions and relief sculptures celebrating the victory.

And, like the pyramids, this artwork has multiple purposes beyond its main commemorative one. It’s massive size (the largest of all the Roman triumphal arches) and its elaborate design (using three arches instead of one) were intended to impress all-comers with Constantine’s new absolute power. (2)

- Storytelling

Commemorative artworks, as part of their function, often tell specific stories as well. As mentioned above, the Arch of Constantine used both inscriptions and relief sculptures to tell the story of Constantine’s victory over Maxentius. Storytelling, then, is another purpose for making art.

The sculptural friezes on Constantine’s arch, for example, illustrate the stages of the victorious event by depicting the emperor’s army leaving Milan, Verona under siege (shown below), and the final battle of the Milvian Bridge.

The two identical inscriptions on the arch also document Constantine’s victory, and they say something like this:

The Senate and People of Rome dedicate this arch to the emperor Constantine the Great as a mark of triumph because he avenged the State with his greatness of spirit and with his army in rightful battle against the tyrant and all his faction.

But here’s an interesting question to consider. Would this arch have fulfilled its purpose as well with just the inscriptions and no images? Or to make the question more universal and applicable to other works you want to evaluate, how might the purposes of an artwork be fulfilled differently and would that make the piece better or worse? Establishing answers to those questions can move you closer to appreciating the value of the work. In the case of the Arch of Constantine, the inscriptions alone clearly fulfill the commemorative purpose of the piece, but would they have done it as effectively without all the images? What if you couldn’t read or couldn’t read Latin?

Storytelling is also a purpose for much religious art. In the early years of Christianity, storytelling became a major purpose for art, especially since Christianity is based on the written word, and most people back then couldn’t read. So the early Christians relied heavily on images to tell the stories of the Bible.

The Last Judgement sculpture on the west tympanum of the Saint-Lazare Cathedral in Autun, France is a great example of storytelling. (3)

The story (in a nutshell) goes something like this: Jesus told his disciples that he would return at the end of the world and separate the good from the bad. The good would then join him in heaven and the bad would suffer eternal damnation in hell.

Below is a detail from The Last Judgement sculpture shown above, and I don’t need to tell you where these folks are going.

- Interpretation and Expression

The primary purpose of the Last Judgement sculpture was to tell a religious story, but it was also designed to interpret that story in a way that would convince people to be good, or else. The sculptor did a masterful job of interpretation through his use of powerfully expressive figures. He clearly intended to scare people into behaving by graphically depicting fear itself. Interpretation and expressiveness, then, can also be purposes for art.

Understanding that one of the purposes here was to interpret a story in a frightening way, helps us appreciate the artist’s unique expressive style. Without this knowledge, the grotesque figures could appear to us at first as inferior, poorly carved, and grossly distorted. But once we know the interpretive and expressive purposes behind their appearances and can recognize how well the artist fulfilled those purposes, we can begin to evaluate the work differently. Instead of inferior, it becomes powerful and original. From the perspective of fulfilling its purposes, then, this work can be evaluated as high in quality.

In some cases, interpretation and expressiveness are the main reasons for making art. Look at the painting above done in 1912 by Kandinsky. There is a story to this piece, but telling the events of the story is not the focus here. Instead, this painting interprets and expresses the emotions of the story first and foremost. What do you feel when you look at this painting? Confusion? Chaos? Anger? What you certainly don’t feel, I suspect, is calmness, serenity, or peace.

Kandinsky called this work Deluge, referencing the great flood from the Bible. For Kandinsky, the act of painting itself resembled a catastrophic flood. He wrote, “‘Painting is like a thundering collision of different worlds that are destined in and through conflict to create that new world called the work.”

As a musician and a painter, Kandinsky sought to translate the emotional power of music into, what he described as, the “inner sound” of paintings. The world Kandinsky painted was the internal world of feelings, not the world of external appearances. If we looked at this work and evaluated it according to how well it told the story of the Biblical flood, it would fail dismally. But if we evaluated it according to how well it expressed the emotional power of such a cataclysmic event, it would hold up much better.(4)

So, when you seek to evaluate the quality of art, try to discover its purposes, the reasons behind its creation. Seeing how well the work fulfills those reasons is one way to appreciate its value.

At this point in this blog series we’ve discussed what art is and why art is, but have said nothing about beauty. In fact, The Last Judgement sculpture we evaluated in this post could actually be seen as downright ugly. So where does beauty fit in with all this? Isn’t beauty a reason for creating art? Isn’t beauty the main reason for art?

We’ll talk about all this in the next series installment, The Art of Visual Listening 3: Art and Beauty.

Footnotes

(1) If you’d like to learn more about Kufu’s pyramid, check out the article: “The Great Pyramid of Giza: Last Remaining Wonder of the Ancient World” in the online Ancient History Encyclopedia at http://www.ancient.eu/article/124/

(2) If you’d like to learn more about the Arch of Constantine, check out the article: “The Arch of Constantine, Rome” in the online Ancient History Encyclopedia at http://www.ancient.eu/article/497/

(3) More on The Last Judgement at Saitn-Lazare, Autun, France at: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/medieval-world/latin-western-europe/romanesque1/v/tympanum-of-the-last-judgment-autun

(4) More on Kandinsky’s evolution toward abstract art at: http://www.tate.org.uk/whats-on/tate-modern/exhibition/kandinsky-path-abstraction

Image Credits

Liberty Leading the People, 1830

- Eugene Delacroix [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Kufu (Cheops) Pyramid: Giza, Egypt.

- The copyright holder of this work allows anyone to use it for any purpose including unrestricted redistribution, commercial use, and modification.

Arch of Constantine: Rome, Italy

- This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported

Arch of Constantine Sculptural Frieze, The Siege of Verona: Roma Italy

- By Ranuccio Banchi Bandinelli – Mario Torelli [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

The Last Judgement Tympanum of the cathedral St. Lazare in Autun,Burgundy, France

- By Q. Scouflaire (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Tympanum of the cathedral St. Lazare (detail) in Autun, Burgundy, France.

Sketch for Deluge by Wassily Kandinsky 1912, Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena

- Wassily Kandinsky [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Email Sign-Up

Enter your email address to join the mailing list.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Leave a Reply