The Art of Visual Listening 1: Introduction – What is Art?

(Posted on Wednesday, September 14, 2016)

Introduction

This is the first in a series of posts about visual listening. As an art history professor for, well . . . let’s just say beaucoup years, I’ve taught thousands of students how to look at art and how to learn its visual language. In all those years, though, I’d never thought to call that process “visual listening.” But that’s really what I think it is. So in this series, I’d like to share with you my ideas—old and new—about listening to art.

So, what do I mean by visual listening? (And for all you techies out there, I’m not talking about social media analytics here.) What I mean is the ability to pay attention to and analyze what is visually present in a work of art in order to interpret what that work of art is communicating, to listen to what that work of art is saying.

But before we get into the nitty-gritty of listening, we first need to discuss what art actually is and why it is. We need to consider what seeing is, what perception and creativity are, and how beauty and art don’t always go together. We need to talk about all these things to open our minds and build a context within which our listening can take place. From that foundation, we’ll go on to focus on what is visually present in artworks and how artists talk to us through their unique manipulation of those visuals. But, of course, it only works if we’re listening.

What we will not discuss here is how artists’ lives and the place and times in which they live impact the meaning of their works. All that matters too, but we’ll leave those topics for another day. For now, we are just going to focus on how to use our eyes to listen.

What is Art?

I probably don’t need to say this, but art is everywhere. Everything in your life, excluding nature, was designed by a person—your microwave, your coffee cup, your dental implants—everything.

But just because someone designed it, doesn’t mean it’s art . . . or does it? There’s a popular saying that beauty is in the eye of the beholder. The same can be said for art. It is a collaboration between the viewer and the object being viewed. Or another way I’ve heard it put–art exists when the viewer is prepared to see it as such. So from that perspective, anything made by a person can be art. Here’s an example.

When I was working at the Norton Simon Museum in Pasadena, California many years ago, we opened the doors to the public one morning before our industrial-strength floor polishing machine had been put away. It loomed in the foyer against a wall-sized window overlooking the reflecting pool, its silver body gleaming in the morning sun. The first woman through the doors that day walked straight over to the glistening machine and eyed it with appreciation, walking around it, admiring its sleek texture and complex structure. After a few minutes of concentrated study, she asked the guard who the artist was. For that woman at that moment, that floor polisher was art. (Just to be clear here, the guard at the Norton Simon Museum quickly and kindly set the woman straight and just as quickly tucked the impressive machine out of sight.)

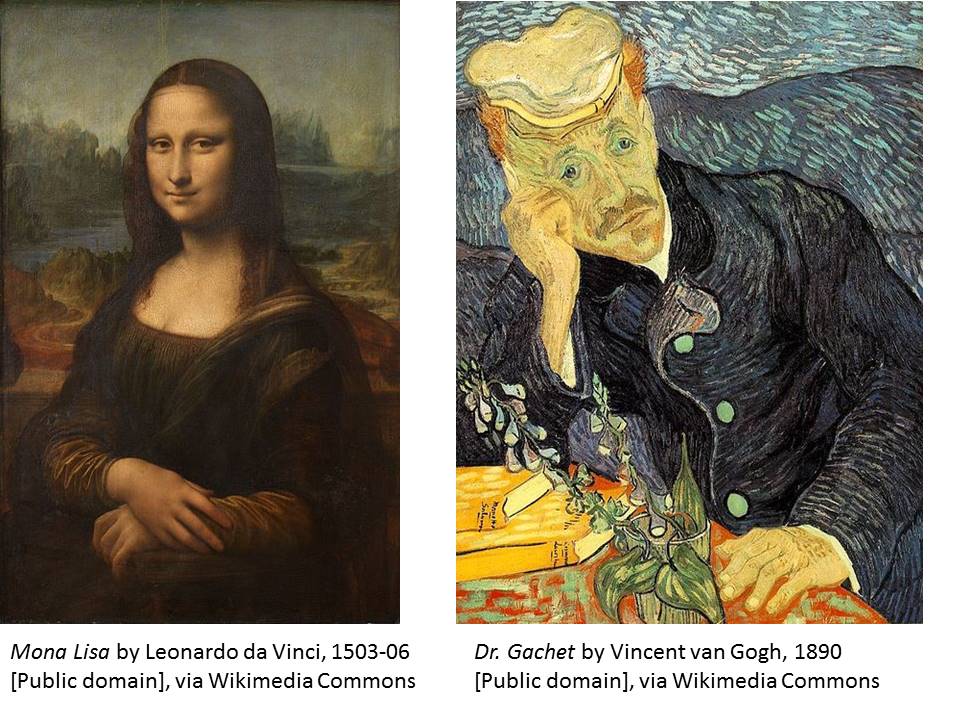

Okay, so anything a person makes can be perceived as art. But if it’s all up to the individual’s perception, if art is in the eye of the beholder, why is some art universally revered while other art is considered less worthy? Why is Mona Lisa a masterpiece and why would anyone spend over one hundred fifty million dollars for a painting by Vincent van Gogh? There must be something to go by, but what is it?

To answer these questions, we first need to know how to evaluate art. We need to know the what, why, how, who, when, and where of the artwork. Armed with that information we can begin to make informed evaluations.

- What is the work made of? Is it oil on canvas, porcelain, ink on paper? Each medium has its own processes, techniques, expressive capabilities, and limitations. How well the artist exploits the materials is one way to judge the quality of an artwork. Does the artist push the materials to new expressive heights? Mona Lisa is an example of that. Leonardo pushed oil painting to new heights with his sfumato technique where he blended lights and shadows imperceptibly into one another, giving his paintings an overall haziness and softness not found in other Renaissance works before him.

- Why is the artist making the work? What is its function? Does it have a practical function (like a floor polisher), a commemorative or religious function (like the Egyptian pyramids of Giza)? Is it telling a story? Or does it want to express abstract concepts like love, power, beauty, or fear? Knowing the purpose of the work helps the viewer to evaluate it in terms of how well it fulfills its purpose. (We’ll discuss the function of art in more detail in the next chapter.)

- How effectively are the visual elements being used (like line, color, and shape)? And how well does the artist combine those visual elements into a cohesive communicative whole? This can make all the difference between a mediocre artistic expression and a powerful one.

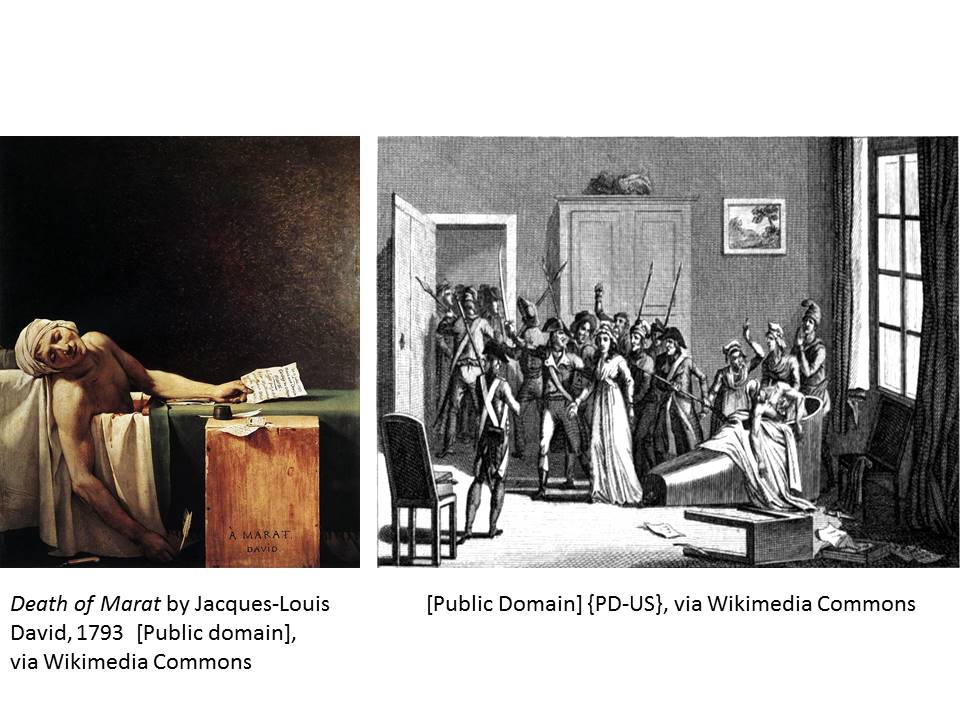

Look at the two images above. The subject of both is the same, Jean-Paul Marat—the leader of French Reign of Terror—murdered in his bathtub. But what a difference between the two visuals. Right away we notice that one is in color and one black and white, and we can tell each artist has chosen to depict the event from a different point in the story, but besides that, the famous painting by David is clearly a more powerful expression. His skilled use of the visual elements and design principles makes his work resonate with us emotionally, while the other work doesn’t. (We’ll discuss the visual elements and principles of design in detail in upcoming chapters.)

- Who is the artist? Art is an expression of the artist’s personality, concerns, skills, and talents. The more we know about the artist, the more we can understand what s/he was trying to do, making it easier to evaluate how well it was done. For example, we cannot evaluate a medieval artist trying to express an abstract concept of spirituality the same way we evaluate a Renaissance artist trying to represent the physical world as realistically as possible. Knowing who the artist was can tell us if s/he was a one-trick wonder or someone who consistently produced quality works. Also important is how much influence did this artist have over other artists? Did s/he start a whole new art movement that others followed? That adds to the value of the work too, demonstrating a unique and historically significant creative leap on the part of the artist.

- When and where was the work made? Africa in the nineteenth century, or France in the eighteenth century, or China in the sixth century? Was the artwork groundbreaking for its time and location, or commonplace?

So, the most highly valued artworks reveal layered combinations of many things: effective use of the visual elements and principles of design; creative manipulation of materials; fulfillment of purpose; powerful and/or groundbreaking expression of the human mind, heart, spirit; and a meaningful reflection of the times and the place in which the works were made. Add to that the time and place in which you—the art viewer—live and you have the whole complex picture.

Remember, in this series, we will discuss only the what, why, and how. We will leave the who, when, and where for another day.

To be continued…

Email Sign-Up

Enter your email address to join the mailing list.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Leave a Reply