The Art of Visual Listening 4: Seeing, Perception, and Creativity

(Posted on Sunday, March 24, 2019)

Now that we’ve examined What Is Art?, Why Is Art?, and the issues surrounding Art and Beauty, it’s time to move on to the process of seeing and the role of creativity in art.

What You See Is What You Get

Let’s begin by distinguishing between looking and seeing. To me, the difference between the two is similar to the difference between hearing and listening, or touching and feeling. The first word in each pair is less involved than the second.

We all look. We have to look to keep from falling over obstacles in our paths, to recognize our friends, to find our way home. In other words, looking is using our eyes to make it through the day. Seeing, though, is a whole other matter.

Seeing is when you recognize your friend and also notice he shaved his mustache. It’s finding your way home while observing the light at that moment makes the tree trunks look pink instead of brown. Both seeing and looking require our brains to process information, but seeing is a conscious, analytical act while looking is a mostly unconscious, automatic process. For me, s

Before we can begin to appreciate and understand art and artists, we must first learn to see, to consciously interact with the visual process as artists do. Once we begin seeing, our standard visual prejudices (likes and dislikes) have a chance to change and our visual perception can expand.

Seeing Is Believing and Other Visual Myth-understandings

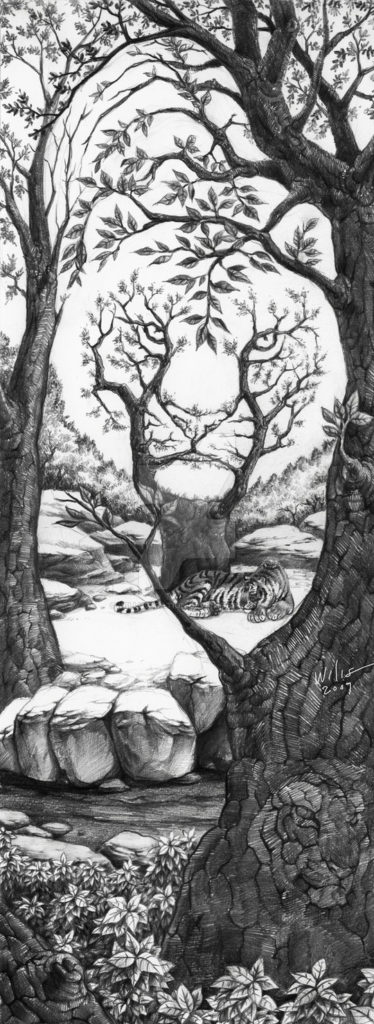

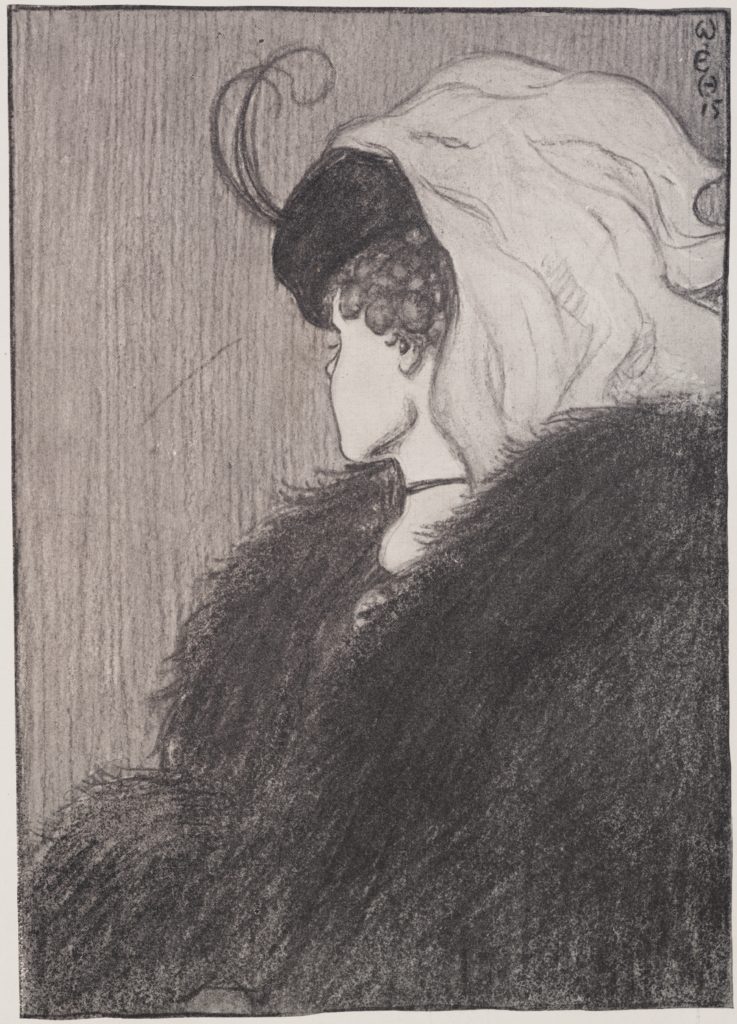

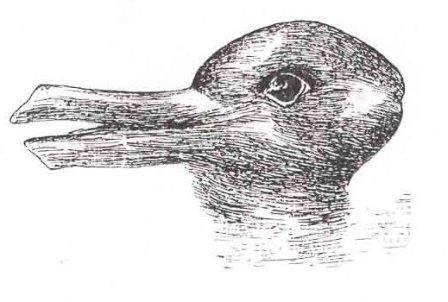

One of the first things to realize about seeing is not everyone sees the same thing or in the same way. Let me show you what I mean. Look at the two images below. What do you see in each?

In the top example, can you perceive both the old and young woman? In the bottom one, can you identify a duck and a rabbit? What you see will depend on your perception—how you process the information your eyes receive. To recognize both images in each example, you must consciously use your brain to process the lines, shapes, and patterns in different ways. In other words, you must force yourself to “see” and through that process, expand your perception.

By the way, did you take a good look at the first image at the very top of this page by the artist known as

A Three-Year-Old Could Do That!

Even as we learn to see and expand our visual perceptions, art can still be difficult to appreciate or understand. Sometimes a work of art looks so simple or crude it seems a three-year-old could have made it. Faced with such an image, it’s easy to feel the artist is having a good laugh at everyone else’s expense. Where’s the art in a scribble? Where’s the skill? In cases like this, it often helps to know something about the artist’s process and what the artist was trying to achieve. In an earlier post, I mentioned one purpose for art can be expression. And artworks with this goal can often be the most difficult to fathom, the most easily dismissed.

Let’s take a look at two examples by two famous twentieth-century artists—Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

The woman in the photograph below is Maria Lani—an aspiring film actress and popular artists’ model in the early twentieth century.

Now, imagine you are an artist interested in capturing the essence of her face. You don’t want to create a photographic likeness. Your expressive goal is to eliminate as many details as you can until you’ve captured her core character with the fewest lines possible. How would you accomplish this? Where would you start? What would your final image look like? (You might even want to take a minute to draw her face with this idea in mind and experience that process of elimination first hand.)

With your image in your head (or on paper) click the link below to see the drawing of Maria Lani by Henri Matisse. It may not look exactly like you pictured it, but knowing the purpose of this drawing and having imagined the process can help you evaluate the piece. The work is simple, but the process of creating it required careful seeing, specific choices, a skillful hand. And it accomplished the expressive purpose—to reveal the underlying essence of that face with the fewest lines possible. Remove any one of those lines and the integrity of the image is lost.

Let’s move on to our second example of art that could easily be dismissed as too simple to take seriously. Imagine you’re looking at a pile of junk that, among other things, includes bicycle parts. Now, imagine making a bull’s head from that junk…….

Got it? Okay. Go ahead and click the link below to see what Pablo Picasso came up with in

Aw, you say, anybody could have done that. Yes, just about anybody could have put the bicycle handlebars and seat together to make a bull’s head, but few would have imagined it first. It took quite a leap of the imagination for Picasso to see a bull’s head in

Side Note: I know I said this blog series wasn’t going to cover when and where artworks were made, but I just can’t let this one go by. It’s a great example of how important those factors can also be for understanding and valuing art.

Picasso made his Bull’s Head in 1942 while living in Paris during the Nazi occupation. Art supplies were severely limited during the war, but that didn’t stop Picasso. He kept on working with anything he could find. And although the Nazi’s offered him special treatment if he would collude with them, he never did, continuing to staunchly oppose their ruthless regime. Looking at the Bull’s Head from this angle adds another level of appreciation. It becomes more than just a brilliantly imaginative work. It also stands as a protest—an unwillingness to acquiesce to a brutally bull-headed regime.

A Parable about Creativity

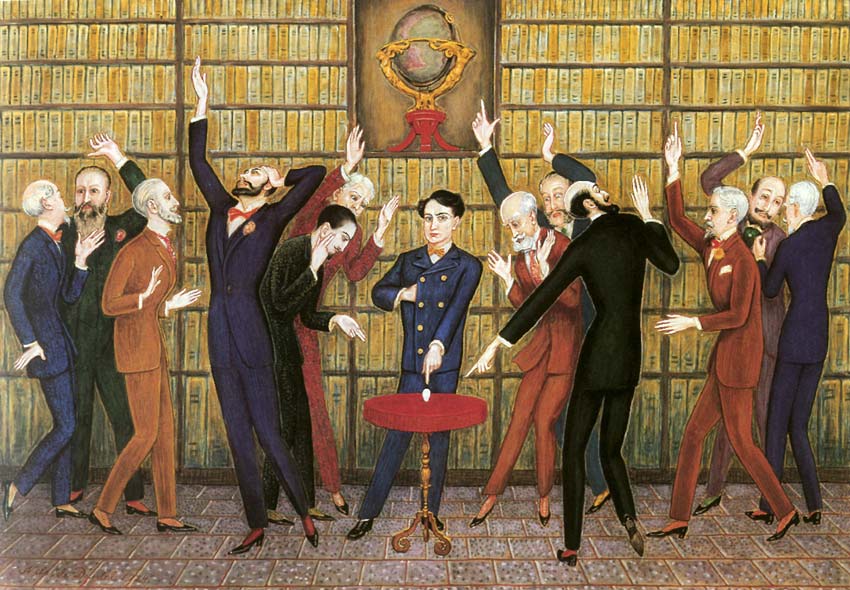

Christopher Columbus is dining with a friend in Spain after successfully sailing to the Americas. The friend, unimpressed with Christopher’s accomplishment, tells him, “Anybody could have done that.”

“Really?” said Columbus.

“Absolutely!”

“You’re sure?”

“No question about it.”

Christopher then ordered an uncooked egg and handed it to his friend. “I’d like you to stand this egg on end,” he said.

The friend took the egg and said, “Don’t be ridiculous, it can’t be done!”

“Really?” said Columbus.

“Absolutely!”

“You’re sure?”

“No question about it.”

Columbus tapped the end of the egg to flatten it and then stood it up.

“Anybody could have done that!” the friend roared.

“Yes,” said Columbus, “but only after someone showed them how.” (1)

Creativity versus Skill

I love that parable. It’s such a fun example of creative thinking. And it also beautifully highlights the difference between creativity and skill—two things sometimes confused in art. Skill is about proficiency, how well one can do a specific activity. Usually, to be skilled at something, one must practice that particular task repeatedly. I think we all can agree it took no great skill for Columbus to flatten that egg.

Creativity, though, is a different animal. It’s about originality, not proficiency. Creativity is a leap of the imagination. Once the leap is made, it can be copied, perfected and even standardized, but the leap has to be made first. And that’s what Columbus did.

Creativity is the original idea, not necessarily the skillful performance of that idea. Although creative thinking and skill often go hand in hand, they don’t have to. We appreciate Picasso’s Bull’s Head for the leap of imagination it took to visualize it and the powerful message it conveys, not the skill it took to make it.

It’s not uncommon to confuse a skillfully crafted object with creativity. It may be beautifully done but not necessarily original. These are important things to consider when evaluating art. Is it a skillful representation of an existing idea or is it an original idea?

Based on what we’ve discovered so far, it’s clear art can be tricky which makes evaluating it even trickier. For example, if we look exclusively for our own idea of beauty in art, we may miss the real beauty of a piece. If we don’t understand the purpose of an artwork, we may dismiss it as unaccomplished child’s play. If our perception is limited, we may not be able to see the subtle nuances that make a particular work of art rise above the rest.

So, what’s a person to do? Well, don’t despair. Some basic visual guidelines do exist and knowing them can move us one step closer to appreciating the artist’s creativity, skill, and message. Sound helpful? Good, because that’s the topic we’ll begin to tackle in the next post—Form

Footnotes

(1) The egg of Columbus: This story is similar to one published fifteen years earlier by Giorgio Vasari. According to Vasari, the Italian architect Filippo Brunelleschi proposed whoever could stand an egg on end should be chosen to design the dome for Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence. As you probably guessed, Brunelleschi supposedly did what Columbus supposedly did and won the commission for the dome.

Image Credits

The Sleeping Tiger

My Wife and My Mother-in-Law

- By W. E. Hill: [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16926542

Duck Rabbit Illusion:

- [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=667017

Maria Lani photo

- photo for Life Magazine December 3, 1945 https://www.oldlifemagazines.com/december-03-1945-life-magazine.html

Portrait of Maria Lani

- By Henri Matisse

Tête de taureau (Bull’s Head), bicycle seat and handlebars

- By Pablo Picasso, 1942, Musée Picasso, Paris qualifies as fair use under United States copyright law.

The Egg of Columbus

- By Swedish Artist Nils Dardel (1888-1943) [Public domain], https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=41044295

Email Sign-Up

Enter your email address to join the mailing list.

Buy Now!

Buy Now!

Leave a Reply